Great War Anzacs more adventurous eating abroad than home

Despite responding with more flexibility and appreciation, the Anzacs quarantined their wartime exotic food experiences not as the new norm but as a novel other. This reinforced Australian identity within a British-imperial worldview, with the soldiers using overseas service to broaden their understanding of culinary culture.

These are the major findings of a paper by our Anzac historian Professor Daniel Reynaud and wife Emanuela, based on their reading of the diaries, letters and memoirs of more than 1000 members of the Australian Imperial Force.

Catering

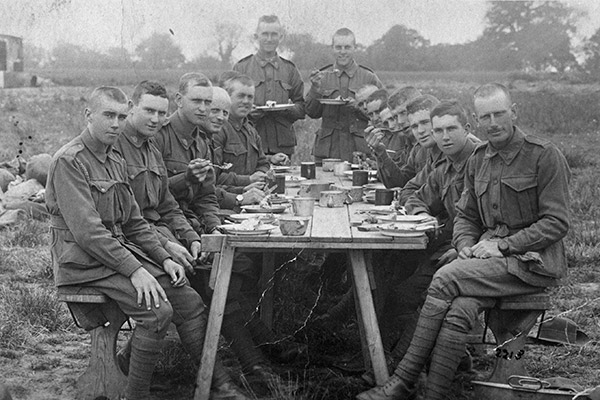

Army catering fascinated the Anzacs, with one writing to his family about mealtime bugle summons, terminology such as “messing,” eating in the open and washing his own dishes. Another first? Cooking their own meals when the army could not, especially at Gallipoli. The irony of manly soldiers in the then female role of cooking features in the writings, with some soldiers anticipating their families would make fun of them. Others favourably compared their skills with those of their mothers. The soldiers’ widespread perception of being good cooks, supported by lists of simple dishes they had mastered, suggests two things, write the Reynauds: “the standards of domestic cooking in Australia were often abysmally low” or “[the soldiers’] notions of their ability were inflated by circumstances of war.”

Cuisine

Complaints about army cuisine, particularly in the trenches, were common. Rations modelled on or supplied by the British army included tinned corned beef and wheaten savoury biscuits. These were accompanied by limited servings of fresh meat, vegetables and bread, with storage, transport and theft interrupting supply. But with food ranking below ammunition and horse feed on the army’s scale of priorities and minimally-skilled cooks trained to emphasise economy over palatability, “relentless meals of bully beef, biscuits and stews were the standard fall-back dishes.” This “unremitting dreariness” motivated the Anzacs to try other foods and food contexts.

Civilian company

With two-thirds or more of their time away from the front—in training camps or hospitals, on leave or resting behind the lines—soldiers could spend months in a location, creating many opportunities for tourism. Their generous pay of six shillings per day—the British received only one—enabled them to more fully sample foreign experiences. Dining out became a common practice, with civilian company—providing surrogate mothers and siblings and the “powerful attraction of young women”—as “important as the food itself.” Some Anzacs ate in exclusive establishments, adding the novelties of glamorous fashion from upper class dining companions to that of exotic dishes. The Reynauds write about a “sense of delight, not just of the soldier in the lap of luxury after the hardships of the trenches, but also of the colonial revelling in elite tourist experiences.”

Change

The Anzacs “confronted not just a range of new foods, but also familiar ingredients prepared in new ways, giving birth to flavours and food experiences that terrified some and tantalised others.” Soldiers wrote positively about “melt-in-the-mouth” fresh dates in the Sinai and Palestine, frog’s legs in France and flaming brandy pudding in England, but few found snails appetising. Garlic and “smelly” French cheeses receive no mention.

“Peculiar” experiences such as buffet dining, coffee drinking at the end of meals and tearing food apart with bare hands at feasts with Bedouin sheiks challenged some soldiers, although they usually welcomed the French practice of adding a dash of rum to coffee.

The sampling brought better nutritional balance and added variety to their diet. It helped the Australians, who “appear to have emotionally managed the changes better than the more conservative British.”

Impact on culture

While many of the experiences were “pleasurable and prestigious,” the long-term impact on Australian food culture “appears slender.” Who cooked and what they cooked did not seem to change once the soldiers returned home. Women got the blame but men, who could have insisted on new cuisines, set the food agenda. “The necessary cultural frameworks of new ingredients, recipes and traditions for innovation were absent, making change harder to introduce,” write the Reynauds.

And dining out? Perhaps the Anzacs considered this a tourist indulgence, “less needed with mothers and wives to cook for them, and less economically viable once the Great Depression hit.”

With all this food experience on the record, what do we learn from its curation? “Food is so much more than mere nutrition—it’s not just culinary but also socially and culturally important,” says Daniel. “For some soldiers, it reinforced their sense of Anglo-Australianness, and for others, it opened new ways of experiencing food and culture.”

Daniel’s heritage influenced his decision to research the Anzacs and their relationship to food. “I grew up with an acute consciousness of the differences between British–Australian food and the French food we ate at home. The experience of negotiating the differences made me more aware of the dynamic for the Australian soldiers.”

He wrote the paper with Emanuela after noticing all the comments about food in the writings, which he had been reading to explore Anzac attitudes to religion. She teaches hospitality at Charlton Christian College and is “a foodie par excellence and a chef of exceptional skill, so to study something about which we’re both passionate has been enjoyable.”

As has been finding surprises like this: the government advised soldiers to eat chestnuts, stinging nettles and dandelions to supplement protein and greens during shortages of food.

“A broader palate? The new and exotic food experiences of the Australian Imperial Force 1914–1918” has been accepted for publication in the journal Food and Foodways.

Invite Daniel to your classroom

You’re a history teacher who likes to engage students. Invite Professor Daniel Reynaud to take a lesson about the Great War Anzacs, their representation in early Australian films, or their attitudes to religion and food.

CONTACT USShare